1.5 - Create a giant bureaucracy while paying academic staff to fill in web forms and watch training videos

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not reflect the views of any affiliated institutions unless explicitly stated.

The unique benefits that we associate with universities are fundamentally the product of teaching and research. To do this teaching and research we employ academic staff. No academic staff doing teaching and research means no university. So, as senior management are rolling out wave after wave of changes to university systems, at a minimum, they need to make sure the changes work well for academic staff, listening to their concerns about workload and protecting the time they can spend actually doing teaching and research. A really bad idea, on the other hand, would be to not only implement a series of poorly justified changes without proper consultation, but to do so in a way that shifts more and more administrative tasks onto academic staff. This idea fails on multiple levels. It fails because it means academics will be doing less teaching and research, less of the things that make us a university. But it also fails because a specialist administrator can generally do the work more effectively and efficiently than an academic, who’s trying to do it alongside teaching, research and a long and diverse list of other administrative tasks they’ve been asked to handle. And on top of that, it fails because, while the objective is often cost saving, you generally have to pay an academic more than an administrator to do the work. All this means shifting administration from support staff to academic staff would be just how not to run a university. Unfortunately, once again, this seems to be exactly the approach taken by the change management programme at my university.

It’s clear that the senior management team at my university are at least aware of these concerns. The aforementioned ‘Getting it Right’ piece, for example, includes a text box outlining ‘Auckland’s Design Principles for Administration Service Delivery’. Principle number two is ‘Reduce the administrative burden for academic staff and Heads of Department.’ This sounds great - it’s exactly what academics and Heads of Department have been asking for for years, and it’s right there at number two on the list - thank goodness! But if we look a little closer, there’s cause for concern. The other five design principles seem to push in a different direction, driven by a belief that what our university needs above all, is centralisation and standardisation in the name of efficiency.

These ‘design principles’ are revealing enough about the philosophy guiding senior management to be worth a short digression. Principle one seems pretty reasonable - ‘Make the best use of resources, skills and expertise (economies of scale and skill)’. Who wouldn’t want to make the best use of our resources, skills and expertise? But the brackets are telling, in that they already assume a particular kind of solution - ‘economies of scale and skill’ is management code for centralisation and standardisation. Principle three is ‘Administrative staff to report to administrative staff wherever possible’. This one is complex. On the plus side, it can free up academic staff time by offloading training and management of administrative staff to professional managers. On the other hand, it can lead to inefficiencies and a lack of coordination with the academics needing support. Moreover, it takes money that was once used to employ administrative staff to work directly with academics and uses it to employ administrative staff whose chief purpose is to be reported to by other administrative staff (who will themselves report to yet other administrative staff rather than working directly with academics). Principles four and five talk about ‘consistent’ administrative processes and ‘common job descriptions and competencies across the University’. This is what you want if you are planning to centralise and standardise, but doesn’t acknowledge the aforementioned trade-offs that come with centralisation and standardisation, particularly in a university. If processes, structures and roles were heterogeneous before the change program, have we understood why? Maybe there were good reasons for it. That leaves principle six, which states ‘Specialist activities to be undertaken by specialist roles wherever practicable’. This is ostensibly pro ‘specialist roles’, but that would seem to undermine principles four and five. That’s because the intended message here is that while centralisation and standardisation are just good things, specialisation needs justification.

So management kind of talk the talk when it comes to prioritising academics’ time, but they talk some other stuff that seems at odds with this too. Do they actually walk the walk? Or do centralisation and standardisation always win out? Is principle two a genuine commitment or an example of managerial doublespeak, paying lip service to protecting academics’ time while priorities actually lie elsewhere? Actions speak louder than words. So, how have restructures played out in practice?

Let’s return to the SSFR. The case for change promised, among other things, ‘To deliver Student Services that are operationally excellent in both performance and efficiency’ and ‘to support academic leaders to tackle the demands and opportunities of their roles’. True to the change management playbook, after a period of consultation it was decided that what we needed was a more centralised and standardised service. Staff previously in schools and departments were shifted to a Student Hub, and existing central services were to be ‘realigned’ from boring ‘transactional and task-based teams (e.g. admissions, enrolments, timetabling)’ to four ‘centres of excellence’ - a Student Experience Centre, a Student Services Centre, an Academic Services Centre and an Operations Centre. ‘Centres of excellence’ are hard to argue with - who doesn’t want excellence? But one might legitimately worry that a system based around clear functions was being replaced with one where the division of labour was less than clear, particularly to outsiders. Which of the four centres, for example, would you go to for a query about the undergraduate enrolment process?

Whatever senior management was actually trying to achieve with these changes, they probably didn’t have in mind the reaction of a senior colleague of mine who called the enterprise - and I can only use their original phrase - ‘a complete clusterfuck.’ This sentiment (not always put so forcefully) was easy to find across campus in the wake of the SSFR rollout, as staff shared stories about what wasn’t working. My own experience as a Post-Graduate Advisor in the School of Psychology was having to deal with a marked increase in enquiries from confused students who had been misinformed by the new Student Hub (or received no response at all). I have since stepped down from this role, which, due to the increased workload, is now performed by two academics in my School instead of one. One of the most successful teachers and researchers in my School, who would be the last to exaggerate or complain, confessed that their summer had ‘been ruined’ by having to deal with a mountain of administration that had been dumped on them under the new system. And it wasn’t just in Psychology: following the launch of the new regime, a colleague of mine in Philosophy started receiving emails from students across a seemingly random array of disciplines asking for advice on PhD enrolment. We never got to the bottom of the reasons for this, but the current best explanation is that some of the new frontline ‘Student Hub’ advisors hadn’t been trained up on the difference between students wanting to do a Doctor of Philosophy (a PhD) and a Doctorate (PhD) in Philosophy. If this is ‘Getting it Right’ what does an unsuccessful restructure look like?

The above examples point to a failure of change management on multiple levels. A massively costly and disruptive process of change management has taken us from a system that functioned reasonably well to one that is failing to deliver even basic services, let alone the high-falutin’ promises of excellence, efficiency and whole-of-student, student-centric design. In addition, despite ‘Principle Two’ and other statements about the need to protect academics’ time, the new systems appear to do just the opposite - by taking administrative staff out of support roles in schools and departments, much of the work they do must be picked up by academic staff.

Importantly, the erosion of academics’ time on campus isn’t just about who is doing the administration. As well as losing support staff in our schools and departments, the SSFR, like the succession of system reviews before it, asks all staff to interact via an increasing array of clunky automated web forms, janky service centre websites and incomprehensible chains of command. If there is any justification for these new systems at all, it is that they work from the perspective of the central administration (although I have my doubts there too). Certainly, tickets are created, names, numbers and codes are entered in boxes, tasks can be prioritised and the working day is not interrupted by constant requests of varying importance. But from the perspective of an end-user trying to run a course, recruit a postgraduate student, or set up the next research project, the new systems have become frustratingly inefficient at best, and are often just plain farcical. As one colleague put it, each new system seems to have been designed ‘assuming that academics’ time is either infinite or of no value…or maybe both’.

The result of this constant stream of restructures and process redesign carried out with little concern for the people who use the services is an absurdly dysfunctional system that is difficult to describe in words - a kind of Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare that has to be experienced to be believed. The best I can do is offer some of my own recent experiences.

Take PhD enrolment. I had a student arriving from Europe on an externally funded PhD scholarship. Due to field research timing constraints, we needed to start as soon as possible. To enrol they had to first fill in a form. This used to be a Word document that student and supervisor could work through together, soliciting further input where required. The new system is a web form. This sounds innocuous enough - one less Word document for us all to keep track of. But the form can only be viewed by an enrolling student, not their prospective supervisor, and each set of questions in the form is only revealed to the student after the previous set has been answered - whoever included this constraint presumably did so to ensure all elements were filled in correctly before someone could move on, but with no consideration for how the form might be used. Understandably, at each step, my student had questions. They couldn’t find the answers they needed anywhere in the supporting documentation, so emailed their questions to me overnight, and I would try to answer them during my work day. After several phone calls and emails I found someone who knew something about the form. They answered my questions but I could see that this process was going to be a drawn out affair if my student and I could only deal with one road block at a time. I asked whether I could see the form in its entirety. I was told I couldn’t, that it wasn’t the job of the person I was talking to to help me fill in the form (even though they were the only contact I was able to find in the office who created it) and that person X in my faculty could help me fill it in if I arranged a zoom call with them, the student and me. I baulked at the idea of having to schedule a three-way zoom call across time zones to fill in a student enrolment form - this couldn’t be more efficient than the old system. But it was a moot point anyway because when I contacted person X they had never seen or heard of the form before either, nor had their superior and, like me, they couldn’t actually see themselves what questions it contained because they were not a student. In the end, we battled through the form over several days, one page at a time and got it completed. The most helpful advice we received was from another team who said it wasn’t really their job either, but managed to give us answers that were good enough. I breathed a sigh of relief - at least now the application could proceed.

Weeks later I received an email from the student notifying me that the application had still not been processed because one of their reference letters was not received by the Student Services Team. That was frustrating because the referee sent the letter to the required email address weeks earlier, but it was apparently lost. They had already sent their letter a second time but to no avail. The student then took the initiative and sent it to the relevant people themselves, only to be told that the Student Services Team could only accept a reference letter directly from a referee. The referee dutifully sent the letter a third time in a polite email, cc’ing me and the only other contact emails they had been given. Eventually, after weeks of delay, we got the reference letter on the system. Perhaps most frustrating of all, since the candidate already had funding and had only been offered the position after we’d interviewed them and read their stellar reference letters that had been sent to us directly weeks earlier, adding the letter to their application on the university’s system was a completely superfluous administrative requirement.

In response to concerns I and others raised about this process, the new solution is to ask referees to send their letters of reference directly to supervisors, who are then tasked with uploading them on our new PhD enrolment portal. Even if the university’s PhD web systems were well-designed, one might legitimately ask how cost effective it is to be paying academic staff to upload letters of reference from external parties. But it makes even less sense when they have to do it using the same temperamental, unintuitive, patchwork of web portals that external referees and (given how long the process takes) even our own internal administrators seem to have so much trouble with. Spare a thought too for each school’s PhD Advisor/s - academics who are tasked with helping their school’s staff and students through this maze of websites, forms and approvals and, increasingly, performing much of the enrolment process themselves. This is another role that was once handled by one academic in my school, but has since expanded to take up the time of two and, most recently, three academics.

Next, consider teaching. We are required to produce a short ‘Digital Course Outline’ or DCO that describes what a course is about, what ‘Capabilities’ it teaches, and how they will be assessed1. As I was dutifully working through my three courses worth of DCOs before the deadline later that week, my third-year course just disappeared from the system. It wasn’t clear who to ask about this. Was it a technical glitch? Had I accidentally clicked ‘submit’ before it was completed? Was this happening for some other reason? The guidelines for completing DCOs were no help, but do come with a contact number for technical problems. I called it. After over an hour on hold, I spoke to someone who clearly didn’t know what a DCO was. I did my best to explain my situation and what I knew. The guy on the phone said he would escalate the query to ‘level 2’. I said I thought that might be a good idea. Ten minutes later I received a callback telling me that my course had been cancelled and would not be running this year. I said I thought that was unlikely. I run the course and nearly 200 students enrol every year. Our school couldn’t find places for these students without the course. The guy on the phone admitted this was a good point - we decided to go back to level 2. Half an hour later I received a short email with a link to my School’s website and an instruction to contact the course coordinator. I might have done that, except the course coordinator was…me. This can’t have been that unlikely, given that course coordinators are the ones who are supposed to complete the DCOs. In truth, it might have been easier and no less helpful or circular to email myself the original query, but I persevered. In the end, several days later, with the help of one of the few administrators left in my school, we were able to identify the problem - a late exam for second year students necessitated a hack of the enrolment system which meant that all third year courses in my School were temporarily made invisible to students until after the exam, but this also made them invisible to staff.

Finally, take purchasing something for a research grant. It used to be that I could email or call someone in my School who handled this kind of thing and ask them to purchase item X or service Y for my research project. The exchange went something like this:-

‘Hi there. Could we please order an X?’

‘Oh, hi Quentin. Sure. Where should I charge it to?’

‘Can we use the same grant as last year?’

‘Sure.’

‘Thanks!’

The entire interaction was natural, required no special training and might take 60 seconds on my part.

After years of restructuring to achieve greater performance and efficiency, the current process goes something like this:-

It starts with a web form accessed via our ‘Staff Service Centre’ web portal. Any task request requires navigating through a multi-layered hierarchical classification menu to locate the task of choice. The required choices are often unintuitive and establishing the correct path becomes its own challenge - like trying to navigate one of those nineteen eighties choose-your-own-adventure story books to a satisfying conclusion. For example, if you want to set up a Purchase Order for a new subcontractor, should you use the ‘Purchase related queries’, ‘Payment related queries’ or ‘Request to purchase’ sub-menu, under the ‘Shared Transaction Centre’ menu? Answer - none of the above; the correct choice is the ‘New subcontractor PO’ sub-sub-menu under the ‘Subcontractor PO’ sub-menu under the ‘Research Operations Centre’ menu. Each sub-menu generates a web-form tailored to that task along with explanatory notes and links to supporting documents. This sounds workable, except that if you don’t know what to put in any field, you will have to spend time trawling through ‘Quick guides’ and ‘Top tips’ to find the information you need, some of which it turns out, will be out of date. Or you could ask someone with expertise in the area. To do that, you’ll need to navigate to one of the general query tabs, submit a query web form, wait for a response and then start filling in the original form again based on what you’ve learnt. Promised response time to the query form about the actual form is three days, plus another three days once you actually manage to fill in the original form. Also, the forms don’t save and pages time out, so the delays mean anything you’ve entered up until that point will probably have been lost and need to be re-entered.

Once you do fill in the form, three days might seem reasonable, but that’s assuming things go to plan. I recently had an email from a US company who wanted to know why two of their invoices were months overdue - the invoices were the second and third payments of a set of three. They had made several attempts to contact the university’s payments people but had not received any response. If the university had received anything, nobody had told me. When I inquired I was told the company was probably using the wrong contact email. I was sent a pdf guide with instructions on who to contact for unpaid invoices. I emailed the given address, cc’ing the company and apologising for the confusion. Phew - problem solved. But this new contact email bounced back saying it was no longer monitored. I sent an email to the company apologising again for the mix up and wearily opened the Staff Service Centre website, eventually finding my way to ‘Shared Transaction Centre > Unpaid Invoice Related Queries > Overdue Unpaid Invoice’. Half way through this web form it became apparent that I wasn’t going to be able to attach the email correspondence with the company - the form just wanted a single pdf attachment of an unpaid invoice. But I knew we’d already set up a Purchase Order for this many months ago so wasn’t sure if this was the right thing to do. I decided it would be easier to try to talk to someone on the phone. Eventually, I got through to someone who initially asked me to upload the previous invoices and email correspondence into the web form in the Staff Service Centre. I said I’d tried but couldn’t attach the email correspondence. They said someone really should change the system to allow people to do that. I agreed that it might be a nice addition. Eventually, we established that the original purchase order had been cancelled after the first of the three payments (it wasn’t clear why) . After further back and forth, we were able to rectify the situation and, as far as I know, the US company has now been fully paid. There is one final chapter though. A day later, I received an email from the Shared Transaction Centre team telling me that the original payment (the first of the three) had also not been paid and asking whether I would like them to pay it. I pointed out that it had actually been paid two years earlier.

I could go on. My point here isn’t that any one of these instances is an egregious bureaucratic failure or unfixable in isolation - the university is a big organisation and sometimes messages don’t get through or wires get crossed. The problem is that these are not isolated incidents. They reflect a debilitating array of university systems that obstruct rather than enable productivity. Battling to get simple things done has become a normal part of the job of academic staff at my university, wasting countless hours of our time and filling up headspace that should be devoted to actually doing teaching and research.

In Part II, I’ll consider some of the deeper causes of this dysfunctionality, but here I want to briefly address three specific responses that I’ve heard used to rationalise the current broken system. The first of these lays the blame squarely with the end user. Yes, it says, some staff, particularly academic staff, find the systems that emerge from each new round of restructure more and more difficult to use, but the problem is not the systems or the relentless restructures themselves. Rather, it is a lack of knowledge on the part of end users. The solution, therefore, is to require staff to upskill themselves via an increasing line-up of online information pages and help tools, downloadable manuals, cheat sheets, training videos and professional development courses. In other words, to fix each new dysfunctional system that places additional administrative burden on academic staff, taking their time away from teaching and research, those same staff must spend yet more time training themselves to use said system.

Worse still, as if to reinforce the fact that the onus is on the end user and not the service provider, it has become increasingly difficult for anyone with a query about a system to actually contact the people running it for any kind of assistance. There is a certain irony to the fact that, while all academic staff maintain a public facing profile page on the university website, listing their email and phone contact details for all the world to see, in recent years there has been a trend towards making many of the people responsible for running specific services invisible to most other staff at the university - this includes service units whose primary function is, nominally at least, to help academics deliver teaching and research. Indeed some service units appear to have a policy of not giving out individual contact details even when asked. Some at least provide a generic service centre email (or web form), the idea being that issues aren’t lost when a specific staff member leaves or goes on holiday. If managed properly, these generic contacts can work, but all too often they create a diffusion of responsibility and notoriously slow and unreliable solutions. Moreover, by replacing interpersonal interactions and service with impersonal and generic workflows and tasks, the relationship between end user and service centre is somehow inverted. If an end user has an idiosyncratic problem or non-standard request (often when real help is most needed), they can be left with the impression that they shouldn’t really be bothering the people working in these service centres about it - they should just do the training and send through what the service centre needs in the required generic form. Rather than service centres working for end users, end users are working for service centres.

Of course, staff at any large organisation need to do a certain amount of training to learn how key systems work. Indeed, they have a responsibility to familiarise themselves with their organisation’s systems and processes. And we’ve all been in a situation in which a colleague has asked a question about a process that we felt they should really know the answer to. Or been the guilty party ourselves, and curtly told that the information we’re after is clearly stated in policy document HS-7G. But requiring staff to undertake training to use complex or unintuitive systems comes with costs as well as benefits and there are limits on what can be reasonably expected. For one, training takes time. There comes a point when it is more efficient to hire someone to handle the intricacies of a particular process than expect everyone to deal with it. In addition, we’re only human. There are cognitive constraints on how many systems someone can keep in their head, especially idiosyncratic, temperamental, constantly changing systems. At some point it just isn’t reasonable, no matter how much training is available, to expect someone to know it all2.

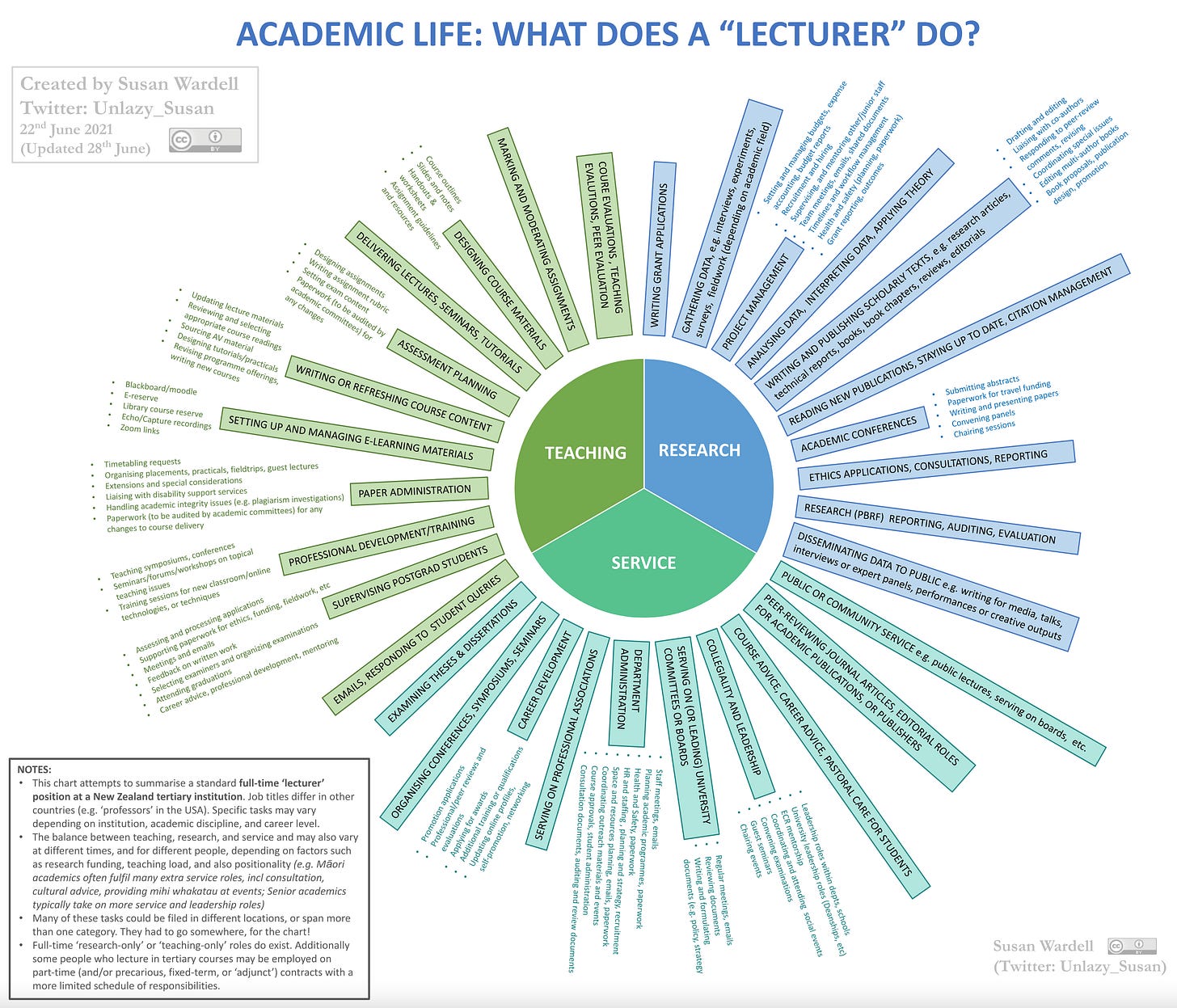

These problems are particularly acute for academic staff, whose roles span almost every aspect of university operations (not to mention their work outside the university). Susan Wardell has captured this beautifully in a diagram from 2021 (see Figure 2)3, which lists the dozens of competing demands on our time. These varied roles mean academics must interact with systems related to processes as diverse as undergraduate and postgraduate enrolments, class scheduling, lecture recording, the online learning environment, supervision, examinations, marking, academic misconduct, marketing, internal communications, health and safety, hiring, media relations, purchasing, asset management, IT management, data management, reimbursements, travel booking, ethics and compliance, to name just a few. At my university, each of these has its own set of forms and web platforms, with names like CANVAS, Inspera, Panopto, LTR, Courseview, Talis, Digital Course Outlines, Student Services Online, Wahapū, DATS, Turnitin, Aegrotats, Faculty Access Portal, InfoEd, Strategic Management Reports, PeopleSoft HR, Peoplesoft Financials, WRB, Sharepoint, CareerTools, Research Outputs, NECTAR, NeSI, the Ethics RM system, DAMSTRA, Concur, and Orbit, not to mention the Staff Service Centre with its 100+ 2nd-level categories to choose from. Then there’s school-specific platforms, external funding and other government agency platforms, and all of this is in addition to the long list of software many of us use to actually do research.

Figure 2 - Susan Wardell’s ‘Academic Life: What does a “Lecturer” do?’4

It’s also worth noting that while some of these platforms are well-designed, most are not the slick, mass-market systems that information economy workers the world over (including academics) all have to work with. OneDrive, GoogleDrive, DropBox, TEAMS, Zoom, Slack and Microsoft Office can all be frustrating at times, but they are generally intuitive, reliable, effective tools with useful help functions (and customer service teams) and on top of all this, they don’t change much year to year. Many university systems, by contrast, run on bespoke in-house platforms that are unintuitive, idiosyncratic, unreliable, and without useful help functions or anybody one can ask for help (our university web page search tool is itself an example of an idiosyncratic, unreliable in-house system). Others are based on cumbersome enterprise software of the sort that Arvind Narayanan likens to the cute baby clothes parents get given by friends and relatives without kids - they might have lots of bells and whistles to get the organisation’s operations manager to buy them, but they are completely impractical for actual end-users wanting to do everyday tasks5.

In addition, partly because they are never quite working properly, university systems are also in a constant state of flux as new features or work-arounds are added, problems patched and one unintelligible menu label replaced with another. On top of that, entire systems are also coming and going all the time. Since I compiled the list of web platforms above, three have been replaced wholesale - InfoEd was been replaced with EndpointIQ, Strategic Management Reports with Enterprise Insights Portal, and PeopleSoft HR with Hono. All this means that even if 18 months ago you did manage to work out the correct procedure for establishing a new course, or buying a large capital item, or sub-contracting someone in the US, the procedure is now likely different.

In the context of this bewildering array of dysfunctional web platforms, portals and pages, simply insisting that academic staff need to complete some training and work it out for themselves isn’t just inefficient, it’s an impossible ask. Yes, there are instructions and guidelines and process flow charts and policy statements online and more can always be made available. But available doesn’t mean practically useful. These days a vast proportion of human knowledge is available to us all online. The problem is knowing what you don’t know, and finding the right answers when you need them. Staff need training of course, but there is a limit to what we can handle, and if the systems themselves are in desperate need of repair, more training requirements just add to inefficiency and workload without addressing the underlying causes of poor system performance. This is, in other words, exactly how not to run a university.

A second common defence from leadership in response to dissatisfaction with each round of change management is that these are just teething problems of the sort we can expect in any change management process, and their significance shouldn’t be overblown. It can, we are told, take one to two years to “embed” the changes, a period sometimes labelled the “benefits realisation phase”. There are a couple of problems with this response. First, saying changes simply need to “embed” while benefits are “realised” frames the functionality that ultimately emerges in the years following a system restructure as the result of some inherent benefits envisioned by leadership. But almost any proposed restructure, no matter how ill-conceived, can eventually be duct-taped together into a workable form. That doesn’t justify the changes, or indicate that its designers deserve special credit for the resulting functionality. A common sentiment among staff on the ground is that, in fact, if things come to function at all, it is despite the latest round of changes made by senior management not because of them. After each successive ill-conceived top-down redesign of roles and processes, the show must go on. So smart, committed, hard-working administrative and academic staff are forced to roll up their sleeves, simultaneously running the new system, while fixing it one step at a time. ‘Do we really need this approval form?’ ‘Could one person handle all queries like this?’ ‘Do we need a second person to help with that?’ ‘Can we change what this menu item is called to make it more intuitive?’ ‘Why has nobody been tasked with this or that important job?’. These are mundane, thankless changes to process made with none of the fanfare and self-congratulatory rhetoric of a university-level review, yet they are the small, stepwise improvements that make our institution function.

Second, “benefits realisation” can take a very long time, particularly if leadership are not willing to listen to staff who identify problems, or if they decide to roll out yet another round of change before staff have had a chance to fix the last round. The SSFR, for example, was rolled out three years ago, but the problems and increased workload in my School persist. Perhaps two to three years is not long enough. What, then, to make of the discussion I had with a long-serving administrator in my faculty, who I thought was looking particularly frazzled when I bumped into them last month? When I asked how they were doing, they said ‘It’s crazy. I just can’t seem to keep up with everything. Ever since FAR things just haven’t worked properly and I’m left doing the work of two people.’ It’s bad enough that this valuable member of the university feels so overworked and unable to change their situation. What’s worse is that FAR (the Faculty Administrative Review) concluded in 2014 - so they’ve been feeling this way for a decade.

I should acknowledge one glimmer of hope. None of what I say above will be news to anyone who has spent time actually talking with rank and file academic and administrative staff on campus. In response, the Faculty of Science, where I work, has asked staff to identify ‘pain points’ in administrative processes. This is a promising development, offering institutional support to those trying to improve current systems in small, reversible ways from the bottom-up. But unless we also curb the relentless bluster of sweeping half-baked, top-down restructures and system reviews that have created the current systems, it is likely this effort is, to put it crudely, pissing into the wind.

A third response to the claim that the relentless programme of change management is a poorly conceived waste of university resources is that, really, it is all about money. Funding for universities in New Zealand (and elsewhere) has been shrinking in real terms for decades and, the argument goes, the successive rounds of restructuring that we’ve experienced are simply a rational response to this financial reality from a savvy management team, a team who’ve allowed us to trim the fat from university operations and thereby achieve greater financial efficiency. We should be thanking management for their heroic efforts, without which the university would be insolvent.

I will come back to the funding question in Part II. Here, I’ll just make two brief comments on this position. First, solvency might be a necessary criteria for good management, but it’s definitely not sufficient. Anyone can cut costs at an organisation. The tricky thing is to do it in a way that avoids, or at least minimizes, harm. And the argument I’ve laid out above is that here, management is failing - each successive round of change is doing real harm to the university’s core mission and to the people who make it up. But worse than this, second, it isn’t clear that these changes really are achieving the promised financial efficiencies. Paying someone on a professorial salary to do administration is a funny kind of cost saving. Yes, our accounting or student enrolments costs may be lower on paper if we’re employing fewer accountants or enrolment specialists, but if the work is now being performed by professors, it’s actually a more expensive system, and, since the professors’ time has to come from somewhere (it isn’t actually infinite) this more expensive system is also delivering less research and teaching.

Moreover, some changes are (ostensibly at least) not about cost saving. The SSFR I’ve been going on about was, according to the case for change from management, explicitly not a cost saving exercise. The new system apparently employs roughly the same number of staff as the old system. Some staff I spoke to about the SSFR have claimed there are now more low-paying roles, a claim that senior management contests, but the point is that it was never sold as a cost saving exercise. This makes the shifting of work onto academic staff and the general dysfunction even more difficult to justify.

But even when changes are sold as about cutting costs through reducing the number of staff, there is good reason to think they are failing at that too. Over the last 20 years, the ratio of non-academic staff to academic staff at my university has actually increased from approximately 1.1 in 2002 to 1.5 non-academics per academic in 2022. It’s true that student numbers have increased during this period too, from about 26,000 full time equivalent enrolments in 2002 to about 36,000 in 2022, which justifies some increase in staffing over the last 20 years. But the increase in the number of non-academic staff outpaces the rise in student numbers. The number of students per academic staff member has remained relatively constant at around 15, while the number of students per non-academic staff member has decreased from 14.1 in 2002 to less than 9.7 in 2022. As a result, in 2022 we employed well over a thousand more non-academic staff (an additional 46%) than we would have if we’d maintained the 2002 ratio of students to non-academic staff.

New Zealand universities appear to be world leaders in this area. A report from the New Zealand Initiative6 found non-academic staff increases across universities in New Zealand, Australia, the US and the UK over the last 20 years, but New Zealand universities showed the highest ratio of non-academic to academic staff of any of the nations examined. This rise in non-academic staffing is even more striking when we consider that many services at our universities, particularly blue collar roles (technicians, cleaners, gardeners etc) have been outsourced during this period and are therefore no longer captured in the non-academic staff totals7. Data from New Zealand and overseas indicates the largest increases have occurred in general advisory and support staff, student welfare and management/executive roles, swamping the much more modest increases, or even declines, in the number of technicians and librarians employed.

To be clear, non-academic staff play a crucial role in the success of any university - and many non-academic staff at my university are going above and beyond to ensure poorly designed systems continue to function. But it is difficult to see how such a massive increase in administrative overheads at our universities is compatible with the supposed efficiency gains of increasing centralisation and standardisation. Nor is there any evidence that this hiring bonanza is in service of design principle 2, to ‘Reduce the administrative burden for academic staff and Heads of Department’. As I’ve argued, the gradual migration of non-academic support staff from schools and departments to more centralised roles has, if anything, pushed more work onto academic staff and forced them to navigate a system that is, at best, impractical and inefficient from an end user perspective and, at worst, fundamentally broken. This only makes the enormous increase in central administration overheads simultaneously more significant and baffling.

There are interesting pedagogical questions around whether this kind of thing helps or hinders student learning, but I won’t get into that here.

Ironically, this is what ‘economies of scale and skill’ from ‘design principle 1’ really means, but such economies apparently don’t apply to academic staff roles.

Readers might wonder why this figure is so great, while figure 1 is bullshit. This figure isn’t bullshit because it includes a lot of actual information and the form maps to function - it presents an array of tasks in three different areas. Yes, it’s a bit busy looking, but even that fits the message.

University of Auckland senior management responded on this point in the New Zealand Initiative report, noting that “While this may be true for New Zealand universities as a whole, this is not true for the University of Auckland. Like many other universities we have outsourced certain activities such as cleaning and specialised maintenance work, but our contracting out rate has declined by 40% over the last 10 years. The University of Auckland has not outsourced several activities that many of our peers have such as traffic and parking, IT services, recruitment, marketing, access and security, student accommodation, health services, retail and outlet management etc. It should also be noted that UoA has one of the lowest contracting out rates of any university that we benchmarkable data for, and a contract out rate at half of the rate of our peer Universities in Australia.”